The 4th Armored Division lost 1,519 men who died fighting with the division during WW2. They were either killed in action on the battlefield or died as a result of the wounds they received during battle. Graves registration encompasses the process of finding, identifying, evacuating, and burying the remains of soldiers who died during the War. In this article, I take a look at the process of graves registration in the 4th Armored Division.

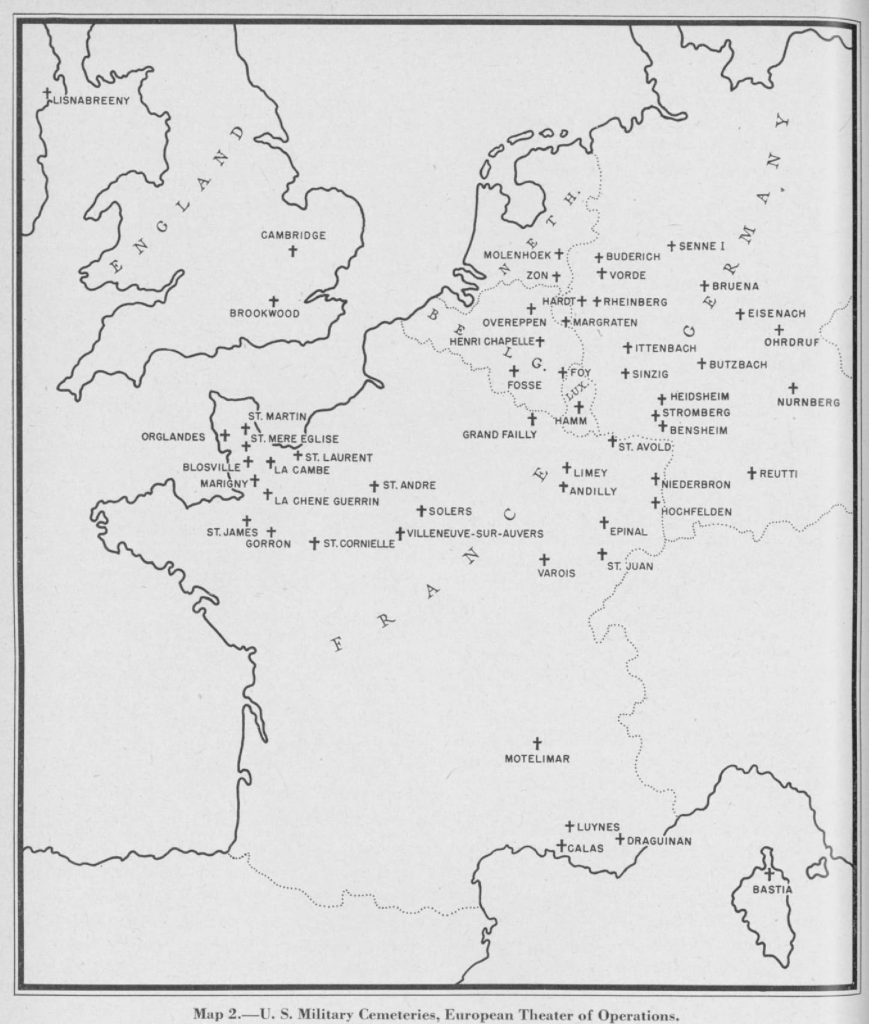

Plans for graves registration in the ETO.

Before D-Day, as a part of all the preparations for the invasion and liberation of northwest Europe, plans had to be made on how the remains of the fatal casualties would be handled. In drawing up these plans, lessons learned earlier in the War were used.

The first document that discussed the procedure to be used in the ETO was “The Handbook for Battlefield Burials and Graves Registration”. This seven-page booklet, which was published on October 1st, 1943, was based on the practices used in Tunisia and Sicily. It was later amended in December 1943.

The final plan for the ETO was published on the 9th of June, 1944. It was called “SOP (standard operating procedure) no. 26: Army Burials, Graves Registration and disposition of Personal Effects”.

The basis for the plan was that each Army would receive 3 graves registration companies, one to attach to each Corps and 1 graves registration company to remain attached to the Army.

The graves registration company attached to a Corps was to split into platoons, with one platoon being attached to a division. This platoon was responsible for the evacuation, identification, and burial of all the fatal casualties of the division in division cemeteries.

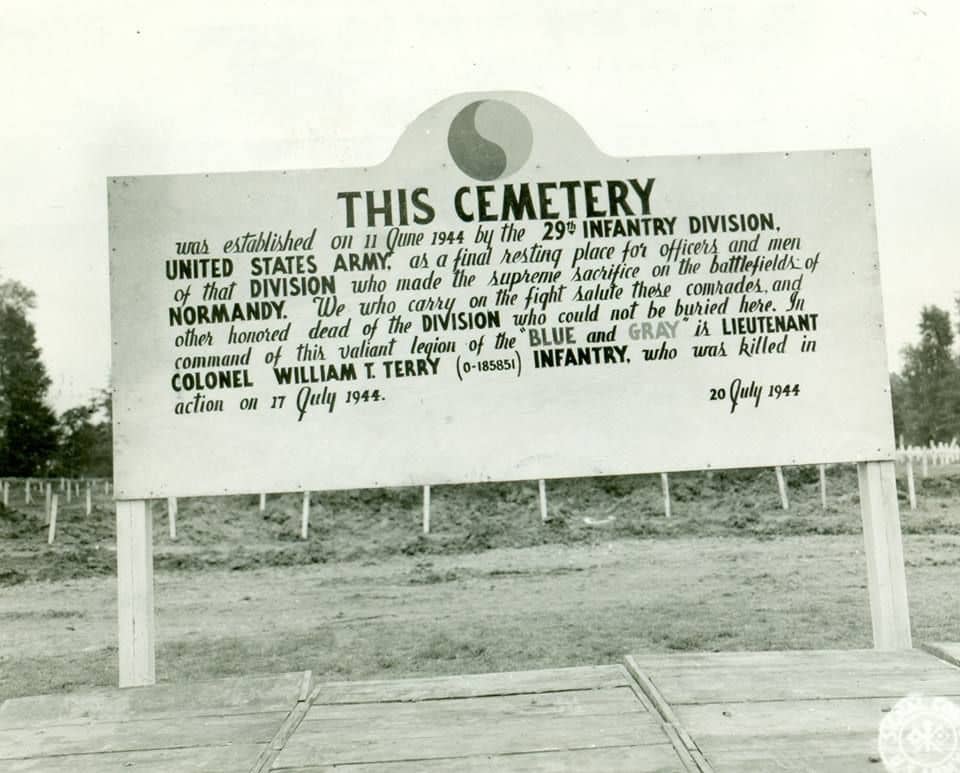

The First US Army (FUSA) was the first army on the continent. It started the campaign keeping the original plan as can be seen in this photo of the cemetery at La Cambe, France. It was a cemetery for the 29th Infantry Division.

US Military Cemetery at La Cambe, France

It was soon found that graves registration platoons were inadequately manned to perform all the duties they were intended to perform. To remedy this problem FUSA started to change the original plan. Evacuation of the bodies from the battlefield became the responsibility of the graves registration officers of each combat unit (from battalion upwards). The bodies had to be evacuated to the collecting point, operated by the graves registration platoons. From these collecting points the graves registration personnel took over the responsibility for the identification and evacuation of the bodies.

Also, in the course of the campaign, FUSA changed the plan and started using corps cemeteries rather than division cemeteries to make more efficient use of the available graves registration personnel.

By the time FUSA fought on the German border, it chose to have one cemetery for the entire FUSA at Henri-Chapelle, Belgium.

Graves registration in Third US Army.

Before it became operational, the Third US Army (TUSA) made its graves registration plans using the lessons learned by FUSA during June and July 1944. It set up a separate division in the Office of the Army Quartermaster specifically for graves registration.

Based on the experience of FUSA, TUSA found that the system of Corps cemeteries was unworkable with the limited graves registration personnel available and it immediately chose to use only Army cemeteries where all the deceased personnel of TUSA would be buried. These TUSA cemeteries were constructed using 300 graves per plot. The graves registration companies establishing these cemeteries could process around 500 bodies per day on average. Often German POWs were used in the digging of the graves.

German POWs digging graves

It also found that: “the graves registration platoon has insufficient capabilities to clear the battlefield. Thus it is the responsibility of the unit graves registration officer to clear the battlefield and evacuate all deceased to the collection point”.

Preparations for this policy were made from May 1944 onwards. On May 25th, 1944 TUSA published Circular No.9 to its troops. In this circular, all units (battalions and higher) were instructed to designate a unit graves registration officer. All divisions were instructed to designate a division graves registration officer whose responsibility was to supervise the evacuation of all war dead to Army cemeteries.

Another important decision was made by TUSA. It made identification of the remains of deceased personnel a function of the evacuation, not of the burial of the deceased. It stated that the responsibilities of the unit graves registration officers ended when bodies, with all identification information, were handed over to a higher echelon. Also, it stated that “if possible, all dead should be identified before evacuation”. This is extremely important because it played a major role in the superior rates of identification of TUSA deceased when compared to other US Armies.

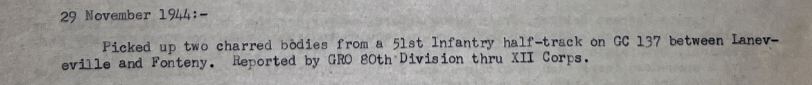

One example of this is when charred remains were removed from the wreckage of burned vehicles. The unit graves registration officer could help with the identification by recording the position of the bodies in the vehicle. This information could then immediately be checked against the unit’s records by the unit’s graves registration officer. This would be far more difficult if the identification process would have been started at the cemetery.

Another development in the identification process, that was initiated by TUSA in December 1944, was the reconstruction of mutilated faces of unidentified deceased. Using the expertise of men who in civilian life had been morticians, to reconstruct the faces of these men, it was then possible for a Signal Corps photographer to take photos of unidentified men. These photos were sent to the frontline units so that they could be shown to the comrades of the men for them to help with identification. These photos were often accompanied by a list of personal items found on the body in the hope that these items might help his comrades in the identification. This process played a significant role in identifying as many deceased as possible.

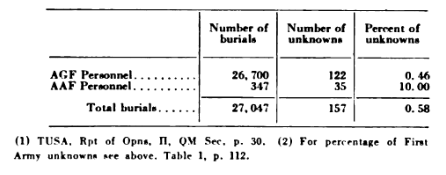

Overall, TUSA graves registration through its vigorous identification process managed to keep the rate of unidentified TUSA personnel at 0.58% (0.46% if we only look at ground forces personnel). FUSA graves registration had a rate of 1.6% overall.

The cemeteries used/created by TUSA for the burial of its troops were:

Blosville, France: this cemetery was established by FUSA on July 1st, 1944. It was taken over by TUSA on August 1st, 1944. It was closed on August 8th, 1944. A total of 256 TUSA soldiers were buried there.

St.James, France: it was established on August 7th, 1944. It was transferred to the Ninth US Army on September 5th, 1944.

St.Corneille, France: the cemetery was established on August 16th, 1944. Burials included 412 Americans, 29 Allied, and 238 Germans.

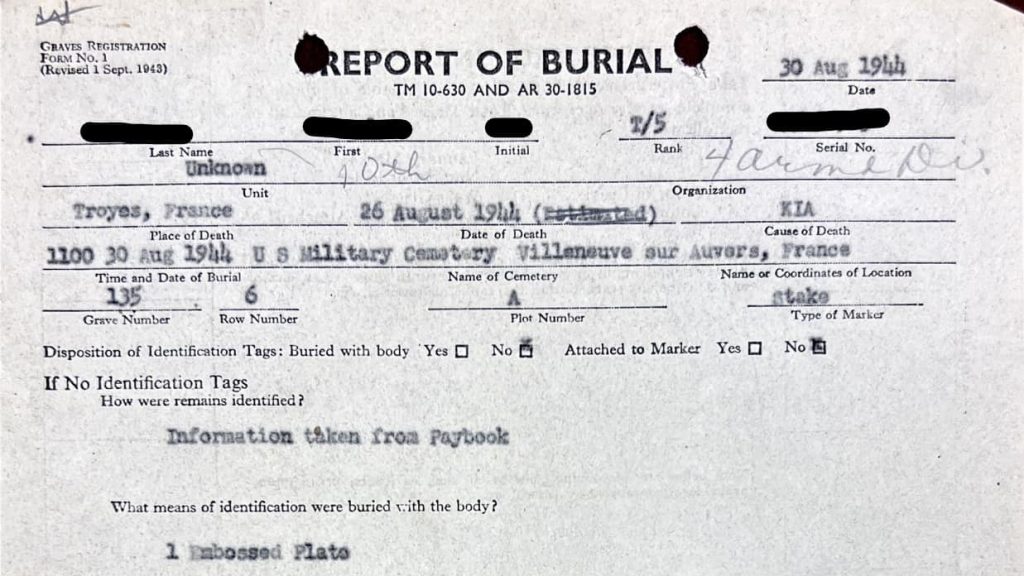

Villeneuve-sur-Auvers, France: TUSA established this cemetery on August 25th, 1944. It was closed on September 6th, 1944.

Champigneul, France: this cemetery opened on September 1st, 1944, and closed on September 20th, 1944.

Andilly, France: opened on September 12th, 1944, and closed on November 5th, 1944 for American burials. It remained open for Allied burials until December 20th, 1944. It was turned over to ASCZ on December 22nd, 1944. A total of 3,307 American and 63 Allied deceased were buried here.

Limey, France: this cemetery was established on November 5th, 1944. It was closed on December 30th, 1944, and was turned over to ASCZ on December 31st, 1944. 5,611 Americans were buried here.

Grand Failly, France: the cemetery was established on December 23rd, 1944. It closed on February 3rd, 1945, and was turned over to ASCZ the same day. Total burials were: 2,741 Americans, 18 Allied, and 1,443 Germans.

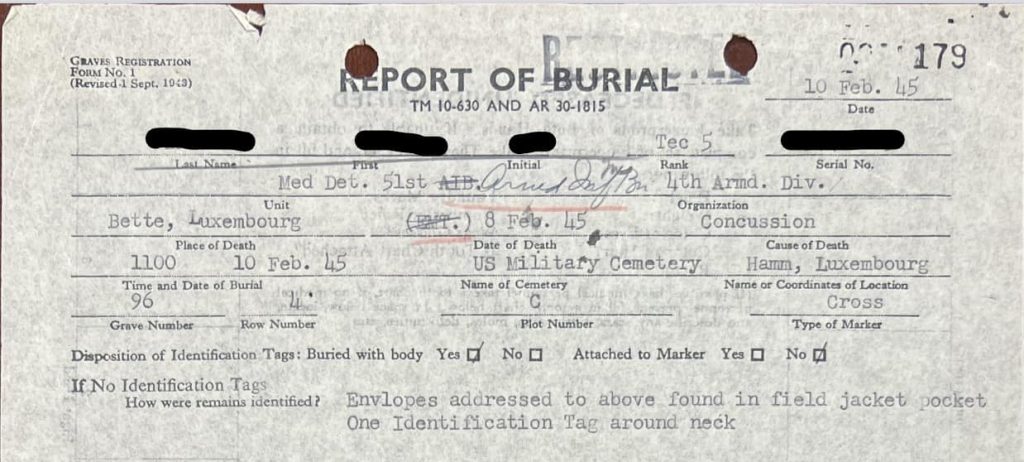

Hamm, Luxembourg: this cemetery opened on December 29th, 1944. It closed on April 1st, 1945. 6,915 Americans were buried here. Also, 5,468 Germans were buried at Hamm.

Foy, Belgium: this cemetery was established on February 4th, 1945. It closed on March 16th, 1945, and was turned over to ASCZ the same day. Buried here were 2,217 Americans, 26 Allies, and 3,396 Germans.

Stromberg, Germany: it was opened on March 26th, 1945. 893 American, 7 Allied, and 508 German soldiers were buried here. It closed on April 11th, 1945.

Butzbach, Germany: opened on April 4th, 1945, and closed on April 22nd, 1945. 687 Americans, 38 Allied soldiers, and 448 German soldiers were buried here.

Eisenach, Germany: this cemetery opened on April 11th, 1945, and closed on April 22nd, 1945. A total of 365 Americans were buried here. Also 8 Allied and 216 German soldiers were buried here.

Nurnberg, Germany: the final cemetery established by TUSA opened on April 19th, 1945.

Temporary American Cemeteries ETO

Unlike all other US armies in the ETO, which had no policy of beautification of the cemeteries, TUSA ordered that the beautification of its cemeteries began the same day that the cemetery opened to receive bodies for burial. The reason for this order was that the morale of both the graves registration personnel working in the cemeteries and the morale of any visiting comrades was improved by immediate attention to beautifying the cemetery. For all other cemeteries, a policy for beautification was only established in October 1944. This policy meant that all other cemeteries were only starting the process of beautification after they had been turned over to COMZ by the field armies.

The process of beautification within the TUSA cemeteries included the installation of a flag pole, chapels, fences, shrubbery, and good roads. Also daily meticulous policing of the area and instructions to keep tools and apparatus used in the construction of the cemetery out of sight (as much as possible) of any visitors, helped in making the cemeteries places of remembrance rather than “construction sites”.

Graves registration in the 4th Armored Division.

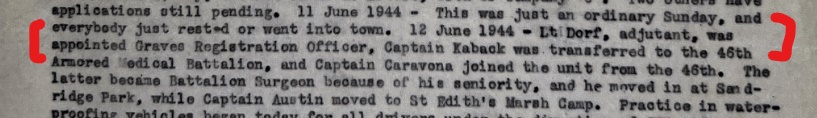

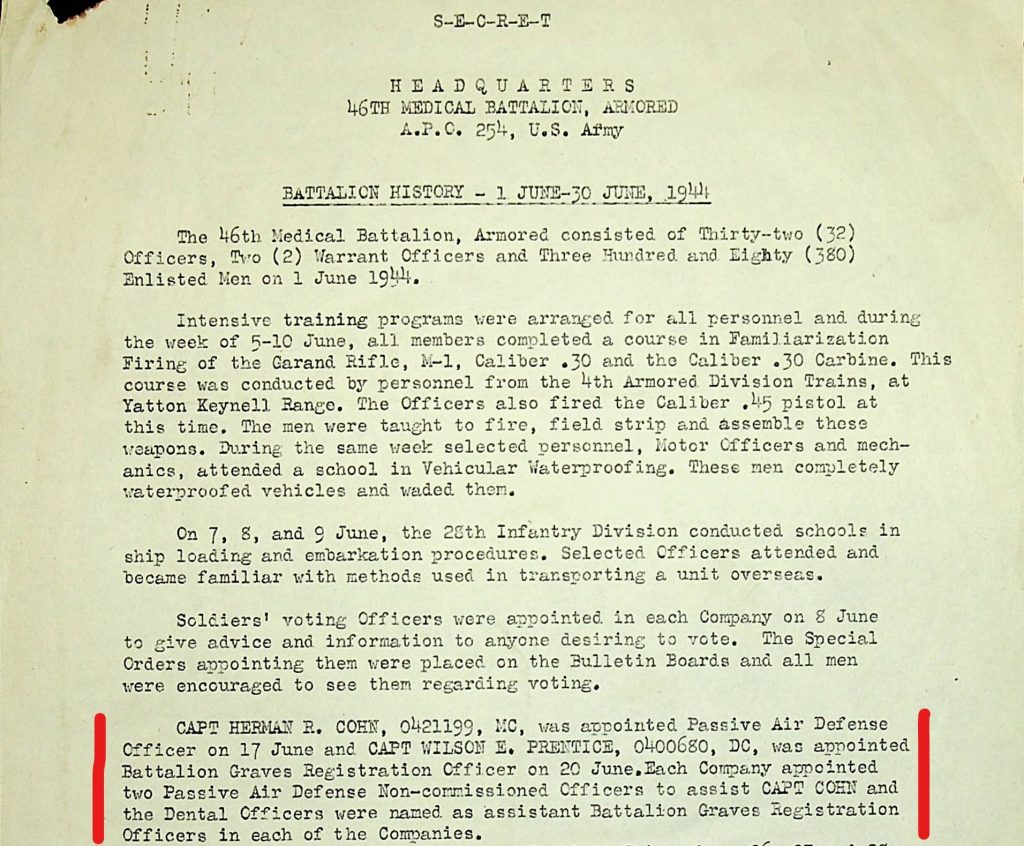

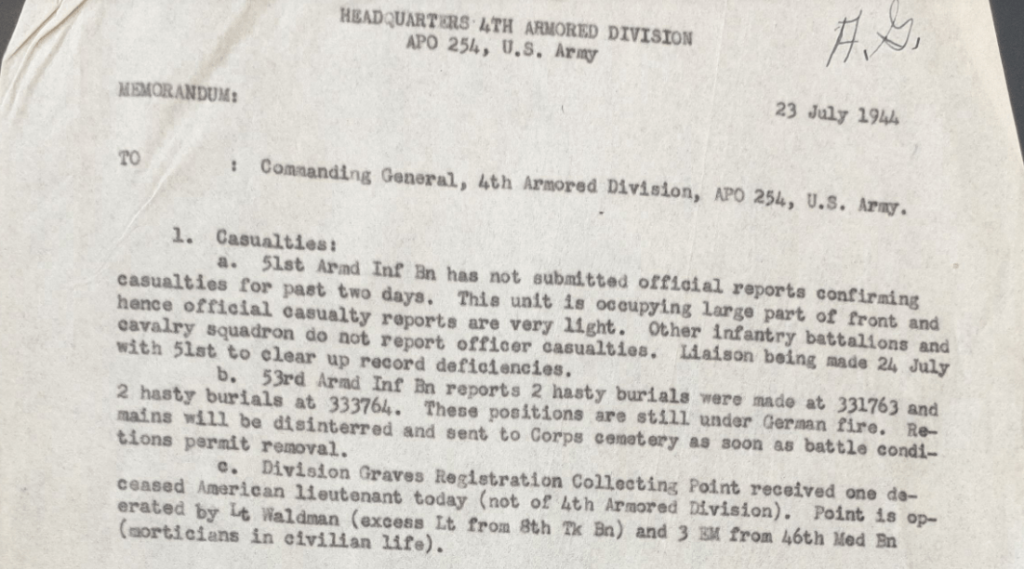

Organization: per TUSA Circular No.9, the battalions in the 4th Armored Division designed a graves registration officer from its staff. Often this was the adjutant of the battalion. For example, the graves registration officer for the 53rd AIB was Capt. Reno Bitzel and for the 51st AIB it was Lt. Dorf.

The 46th AMB designated Capt. Wilson E. Prentice as Battalion Graved Registration officer. He was the dental officer in Company B, 46th AMB. Furthermore, the dental officers in A/46 and C/46 were designated graves registration officers for these companies. Each medical company needed a graves registration officer to supervise the identification and evacuation of the bodies of the soldiers who died of their wounds while under the care of the medical company.

46th AMB history: Graves Registration Officers

When the 4th AD entered combat in July 1944, these were the only official graves registration personnel in the division as the plan then still was that these unit graves registration officers would evacuate the bodies to collecting points manned by personnel of the graves registration platoons assigned from the Third Army.

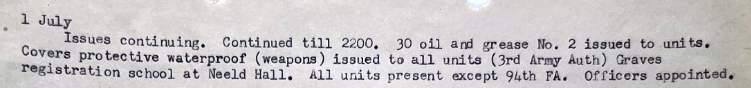

Many of the designated graves registration officers of the 4th AD held a first meeting on June 26th, 1944 in Neeld Hall, Chippenham, England. Also present were Lt.Col. Morris Abrams (4th AD Division Surgeon), Lt. Garnet (CO of the graves registration platoon attached to the 4th AD), and Capt. Hoag (Third Army graves registration officer). At this meeting, Lt. Garnet gave a presentation to instruct the unit graves registration officers.

On July 1st, 1944 a school for the unit graves registration officers was started at the same location.

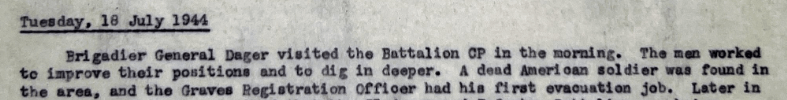

After arriving on the continent, the unit graves registration officers almost immediately had to go to work, clearing their battalion area of bodies.

51st AIB evacuation of the first body

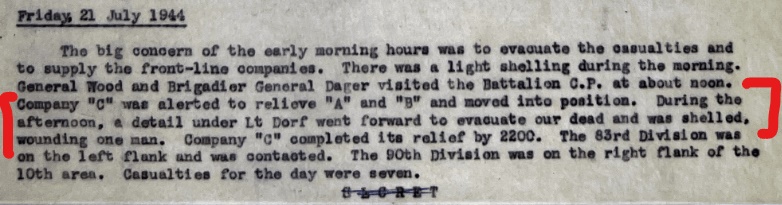

The evacuation of bodies from the battlefield was not without risk. Sometimes the men involved in this somber task were hurt.

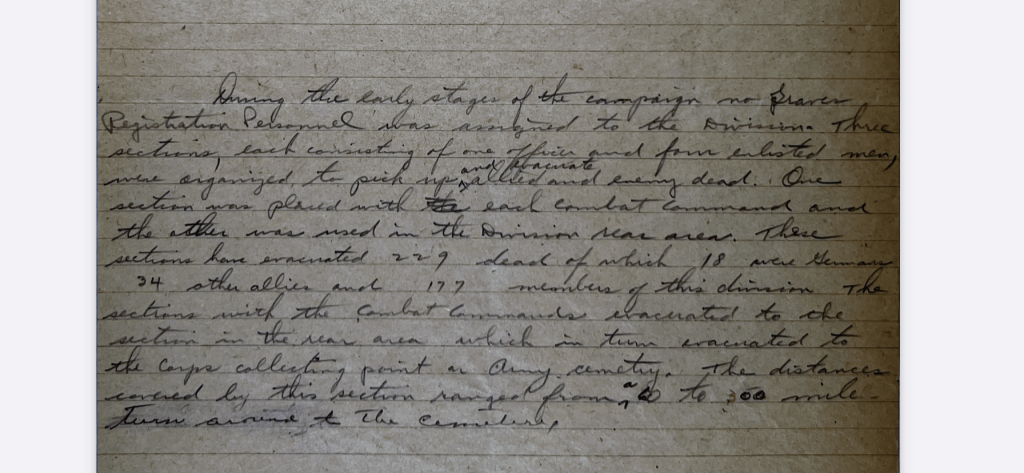

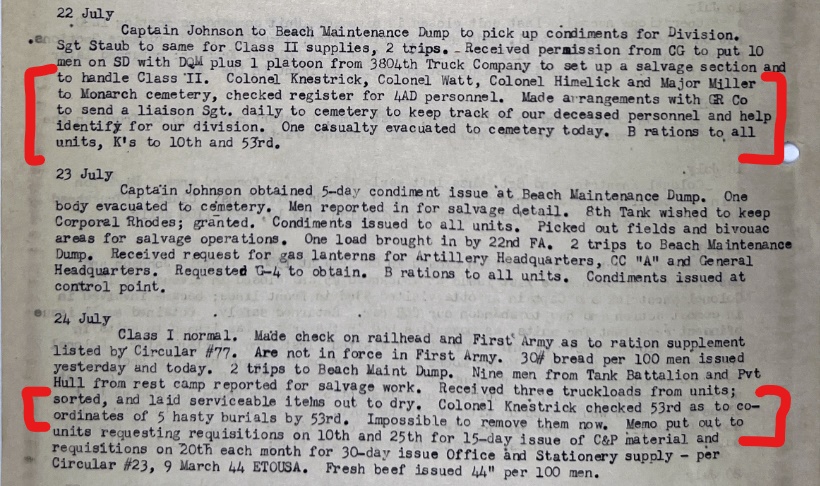

A report of the Division Quartermaster of the 4th AD has a handwritten addendum to it, describing the situation of the division during the early stages of the campaign:

QM handwritten report

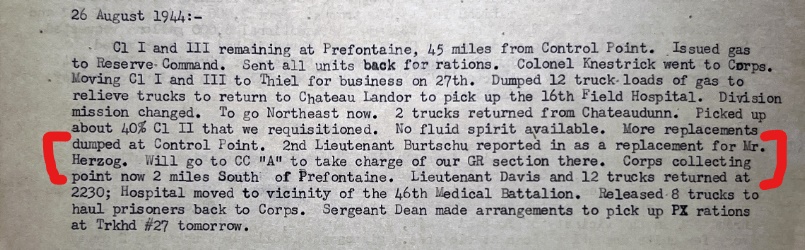

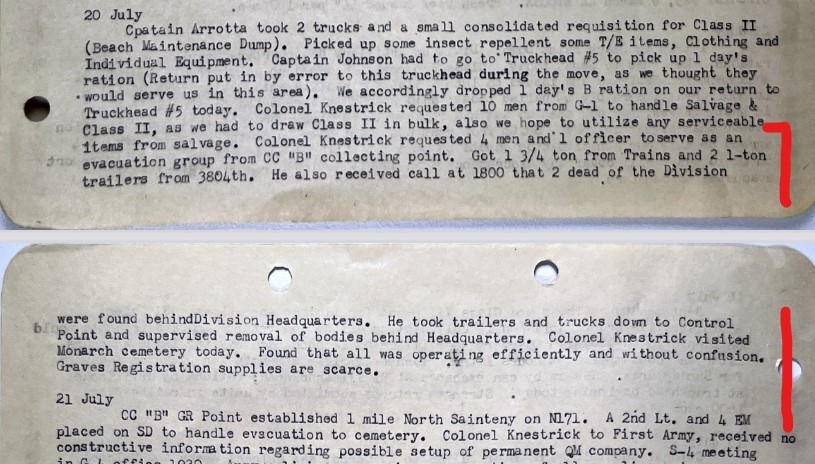

Since no graves registration personnel was attached at that time, the Office of the Division Quartermaster created its own graves registration set-up. It created three sections, each with 1 officer and 4 enlisted men. One of these sections was attached to each of the two combat commands to organize a Combat Command Collection Point. For example, the section attached to CCA was led by (probably)WO William Herzog (he is referred to as “Mr. Herzog”. WO Herzog served with B/46) until August 26th, 1944. He was succeeded by Lt. Burtschu.

The third section organized the Division Collection Point. This was located in the Trains area and was part of the so-called Division Control Point that was organized by the 4th AD QM. The section running the Division Collection Point for graves registration was led by Lt. Walckman, an “excess officer” from the 8th Tank Battalion. He commanded 3 enlisted men from the 46th AMB. They were assigned to this section because they had all been morticians in civilian life. Their expertise proved invaluable in the handling and identification of the bodies brought to the Division Collection Point.

(Possibly Tec4 Eugene Blair (C/46), and Thomas J. Fahey (B/46) were part of this section as they were on DS to 4th AD Tns HQ from 20 and 21 July 1944)

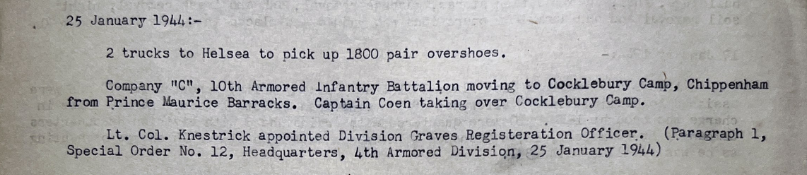

Col. Knestrick of the 4th AD Office of the Division Quartermaster was appointed Division Graves Registration Officer on January 25th, 1944. He supervised all the matters concerning the activities of graves registration within the division.

QM AAR

Evacuation: with this system in place the route of the evacuation of the bodies of the deceased was established. The battalion graves registration officers evacuated the bodies to the Combat Command Collection Points. The Quartermaster graves registration section organizing these collection points evacuated the bodies to the Division Collection Point and the men of this third section evacuated the bodies to either a Corps Collection Point, but most of the time directly to the Third Army cemetery that was open at the time.

For the evacuation of the remains of the deceased, the sections were equipped with ¾-ton trucks and 1-ton (or sometimes ½-ton) trailers.

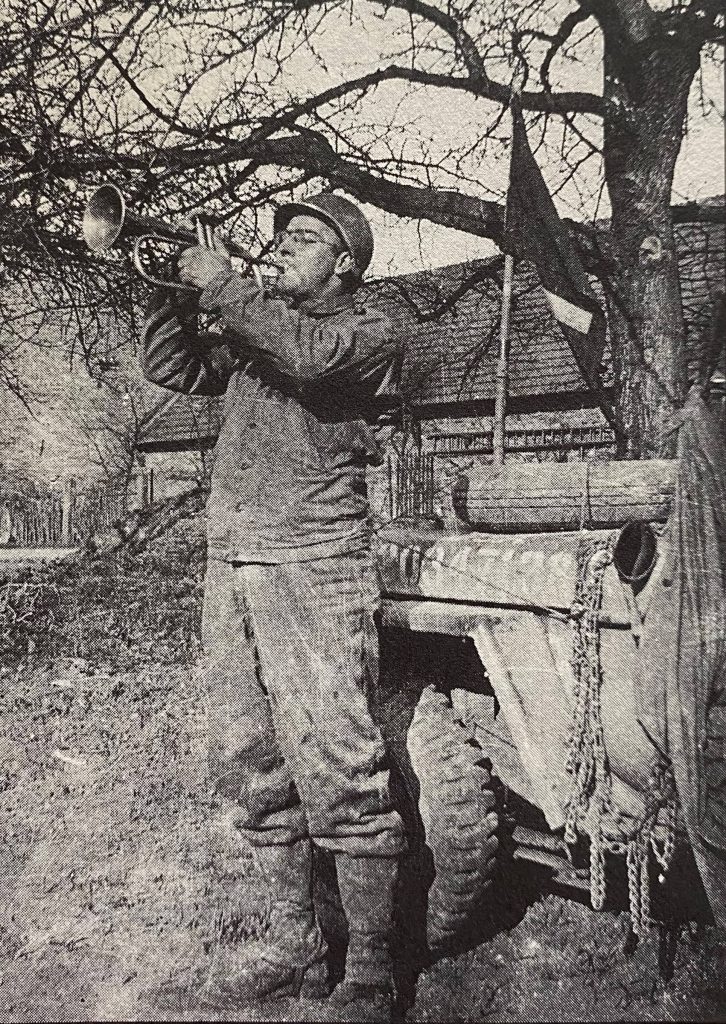

¾-ton truck Graves Registration

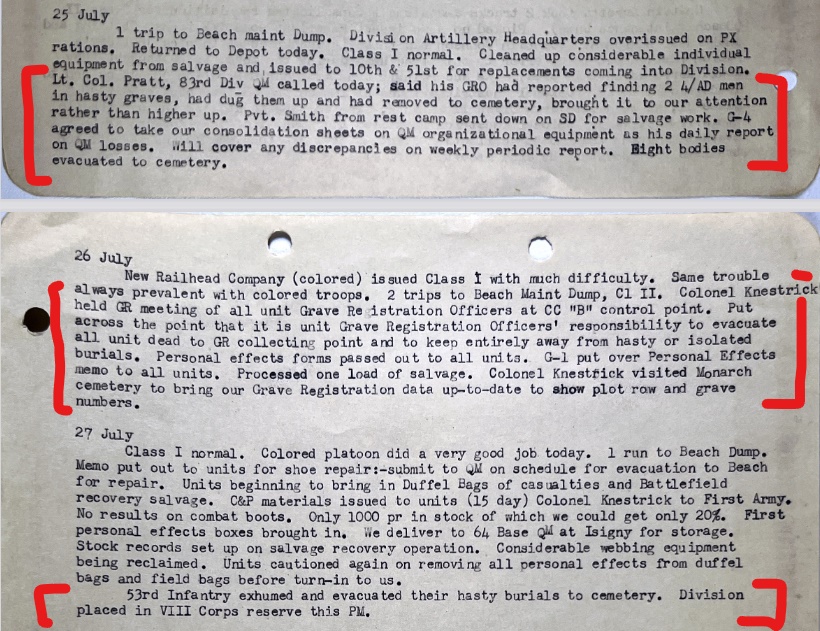

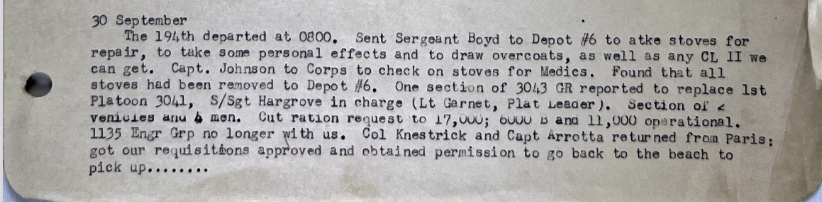

A bit later in the campaign personnel of Graves Registration Companies were attached to the 4th AD. It is not completely clear what their precise role was, working together with the 4th AD graves registration section at the Division Collection Point. They likely played a major role in the identification process before bodies were evacuated to the cemeteries. Perhaps they also played a role in the final evacuation of the bodies to these Army cemeteries.

QM AAR 30 Sept 44

The report of April, 1945 suggests that men of the attached sections of the Graves Registration Companies were not all kept at the Division Collection Point, but were further attached to the Combat Command graves registration sections of the 4th AD.

QM AAR April 1945

This report also shows the risk involved in evacuating bodies from Combat Commands that were advancing rapidly across enemy territory. Unfortunately, I have no report stating what finally happened to the vehicle and the bodies that were lost.

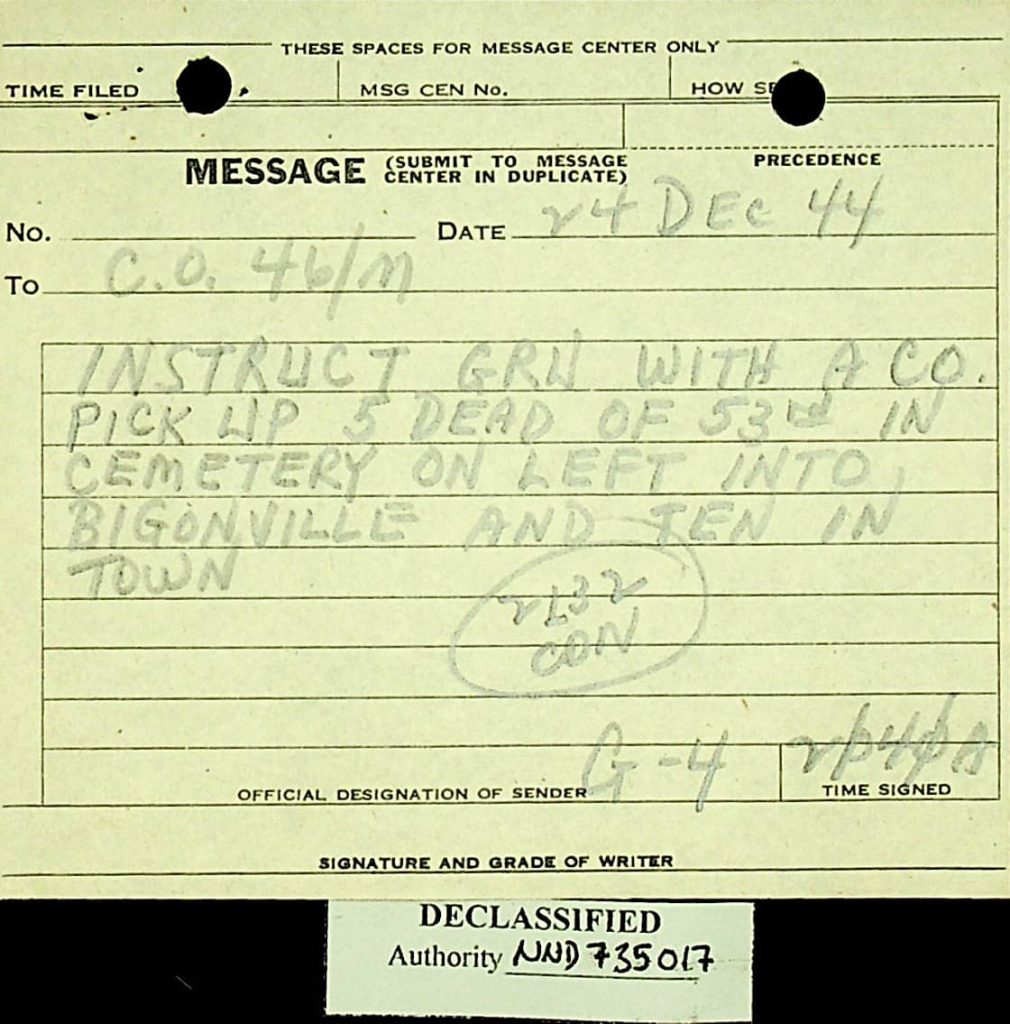

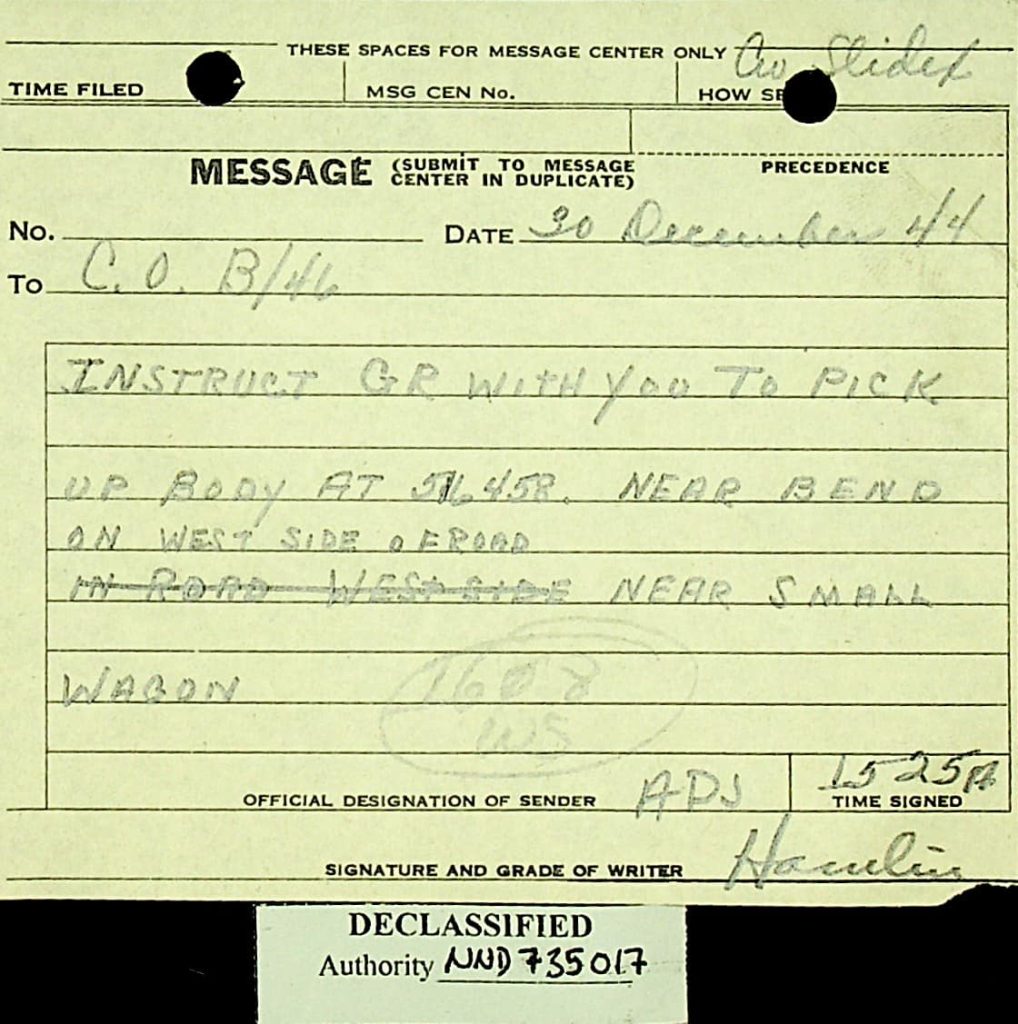

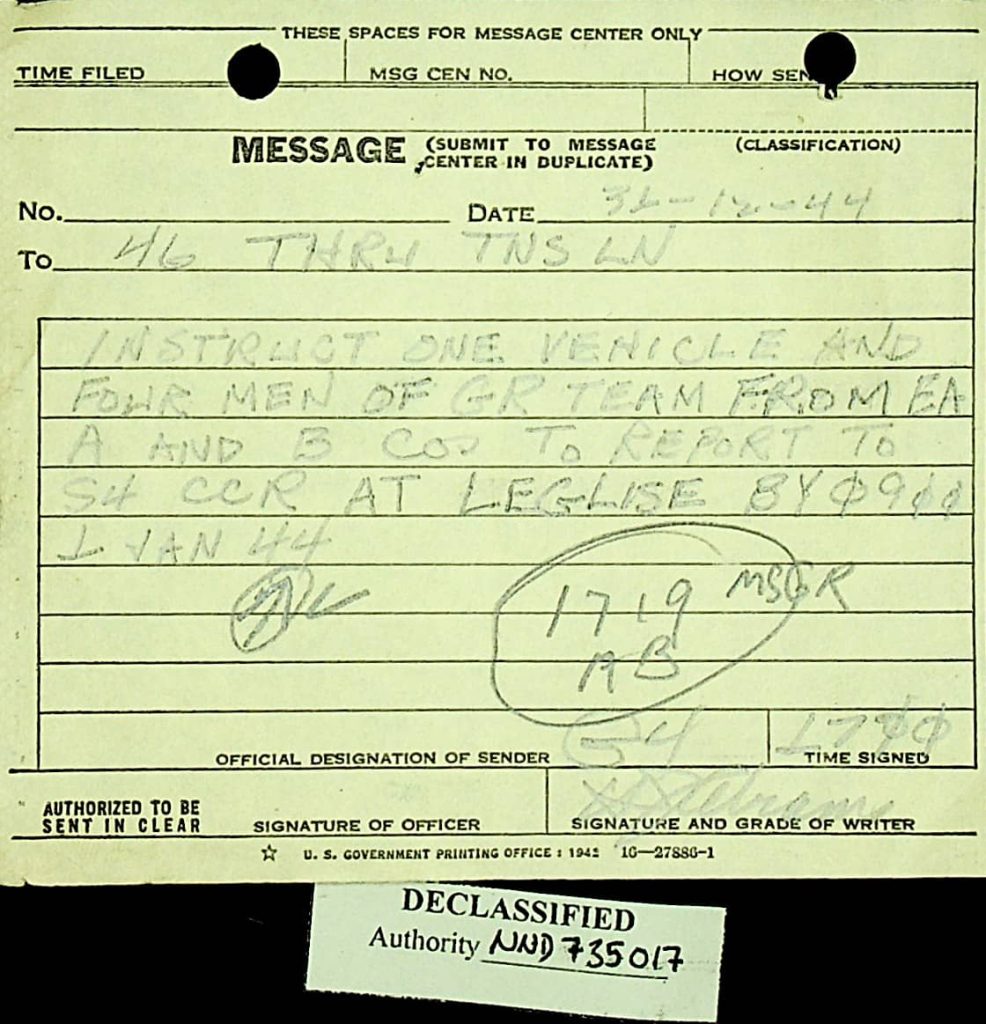

These messages from the 46th AMB make it clear that the graves registration officers of the companies of the 46th AMB played a larger role in the evacuation of the deceases of the combat command they were attached to than just the deceased at the clearing station. They were sometimes instructed to evacuate the bodies of other attached units within the combat command. Evidently, their role was important enough to make Reserve Command need a temporary graves registration section of its own when it became a temporary third combat command during the Battle of the Bulge.

Messages 46th AMB

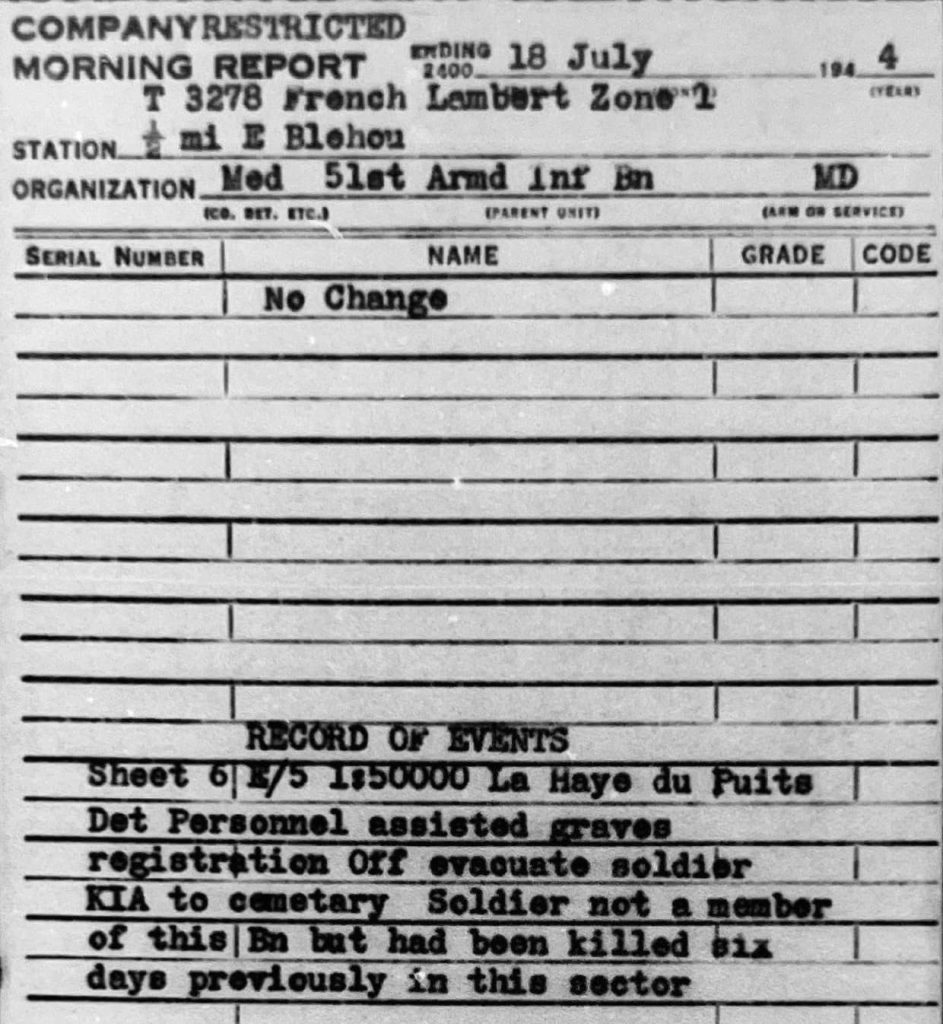

It was certainly not the only time that medics were instructed to assist the unit graves registration officer.

Morning Report MD/51

The task of evacuating the remains of their dead comrades must have been grim. Joseph N. Korzeniowski, medic in Company “C” of the 46th AMB remembered that members of his unit had to pick up dead soldiers by the truckload during summer months and would not be able to breathe the outside air without covering their faces with a handkerchief.

We also get a glimpse of the grim reality of war and the evacuation of the remains of soldiers in the memories that Albert Gaydos, serving in the 66th AFAB, described. Here are his memories of the events surrounding the death of his brother, Sgt. Paul Gaydos.

Memoires Albert Gaydos

Sgt. Paul Gaydos was buried in the US Military Cemetery Grand Failly in Plot C, Row 11, Grave 257 before his body was repatriated home.

Identification: as previously noted, TUSA placed a great emphasis on the proper identification of its deceased personnel. A major part of the effort to correctly identify all bodies was played by making identification a function of evacuation, rather than of burial. As previously stated, by making identification a responsibility of the unit graves registration officer all the knowledge of the unit of its deceased or missing personnel could be used in the process of identification. This important responsibility created a steep learning curve for these officers. A constant process of implementing lessons learned was its result.

This comment, taken from the Division Surgeon’s Journal entry of August 14th, 1944, shows have some of the lessons are immediately used to improve the identification process.

Division Surgeon Journal 14 Aug 44

Primary sources for identification were:

ID tags

Paybook or pay data card

ID bracelet

Emergency Medical Tag

Secondary sources for identification were:

ID tags not found worn around the neck

Personal letters found on the body

Motor vehicle permit

Engraved jewelry

Clothing markings (laundry markings)

For positive identification, one primary or two or more secondary sources had to be present.

Reports of Burial and Identification

Roger Boas served in the 94th AFAB. As battalion adjutant, he was also designated as the unit graves registration officer. In his book “Battle Rattle” he described was this task meant:

“One of the truly bleak roles I had as battalion adjutant was “graves registration”-when officers have to sign death reports of soldiers in their battalion who were killed in action. This is not an area in which you want to make a mistake. That means making damn sure that a burnt corpse is the man you think it is. So I had to kneel down next to what was left of …. and check his blood-spattered dog tag. A grim assignment to say the least” (Pages 142-143).

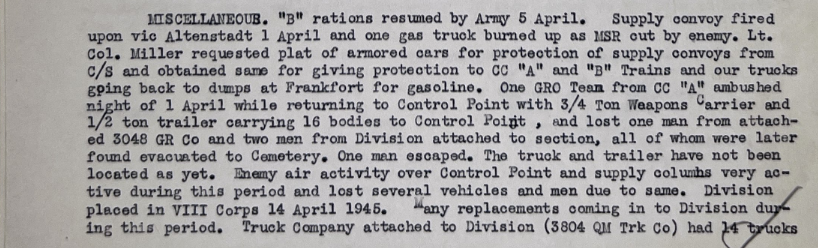

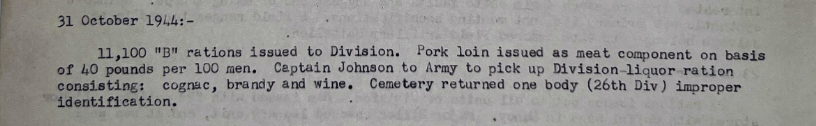

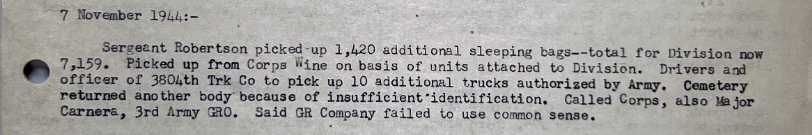

As noble as the effort to properly identify all deceased personnel is, it can go too far. Making identification of the bodies a responsibility of the unit graves registration officers did not mean that all bodies could be properly identified. Unfortunately, this led to some conflicts between the unit graves registration officers of the 4th AD and the Graves Registration Companies organizing the TUSA cemeteries.

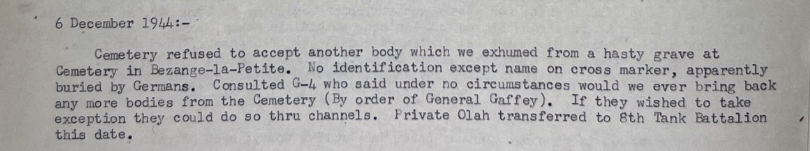

QM AAR 31 Oct, 7 Nov, 6 Dec

As we can see, this issue was finally resolved by orders of Maj. Gen. Gaffey.

Any unidentified body that was buried in one of the Army cemeteries received an X-number. All information that was found that could help to identify the body later was recorded in the file corresponding with this X-number.

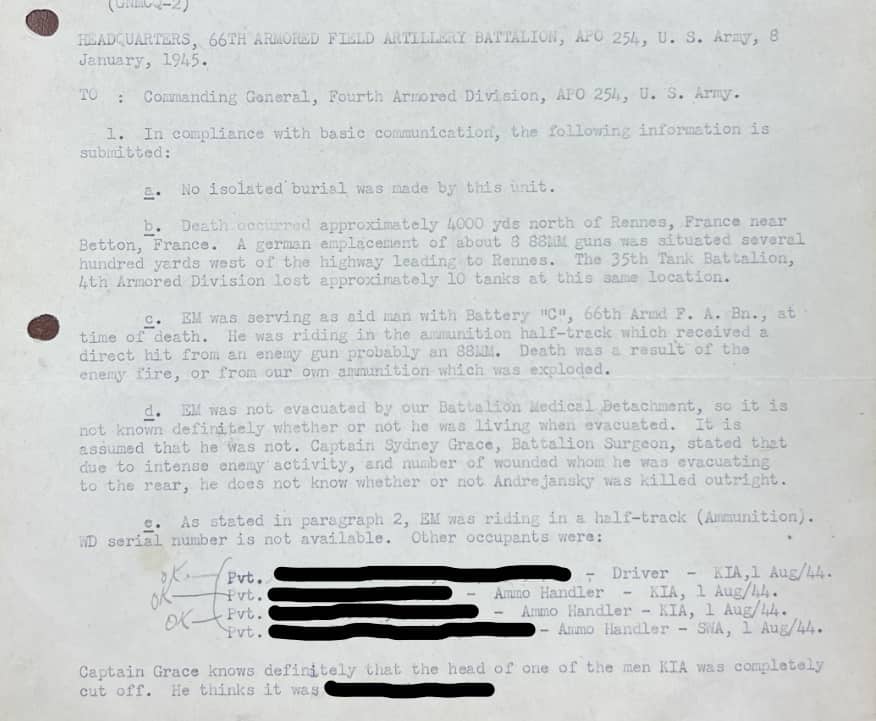

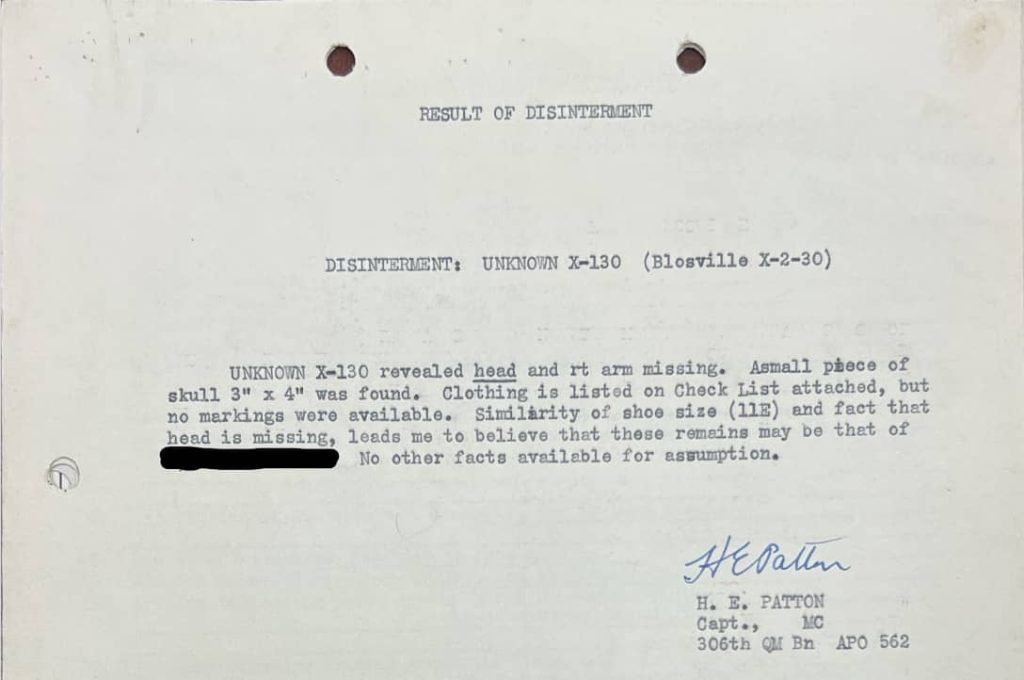

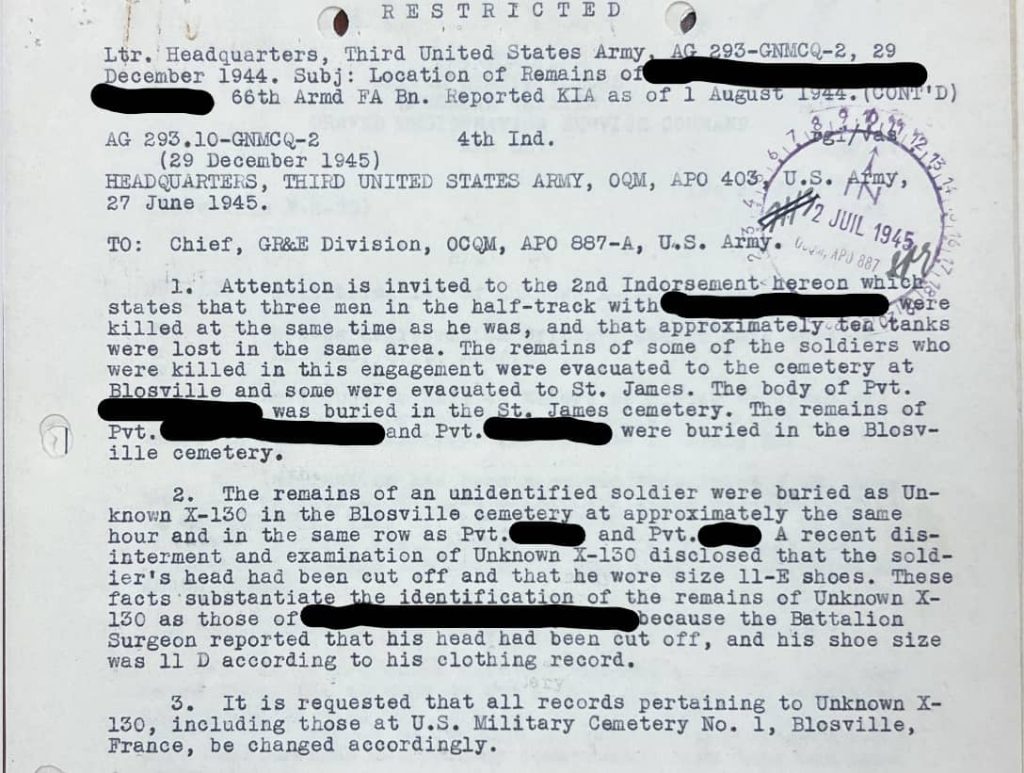

One of the medics of the 4th AD was buried first as X-130 in the US Military Cemetery at Blosville, France. He was later identified by a combination of information about his location in a vehicle, a statement by the Battalion Surgeon, and information about his clothes and boot sizes. This information was checked against the information found after the disinterment of the body.

X-130 Individual Deceased Personnel File

Personal effects

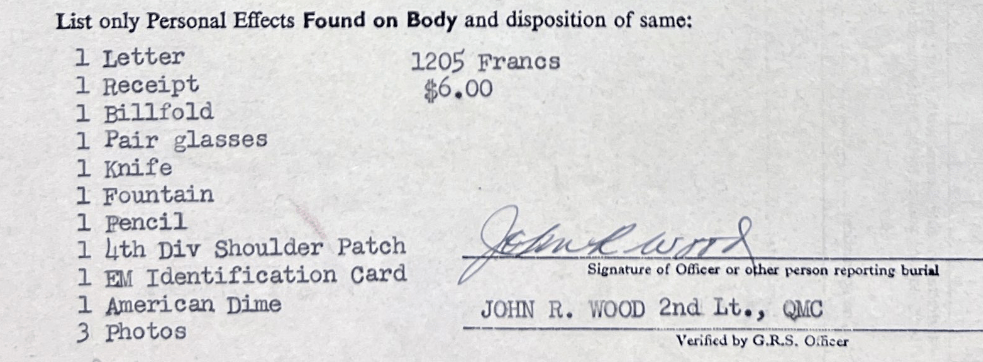

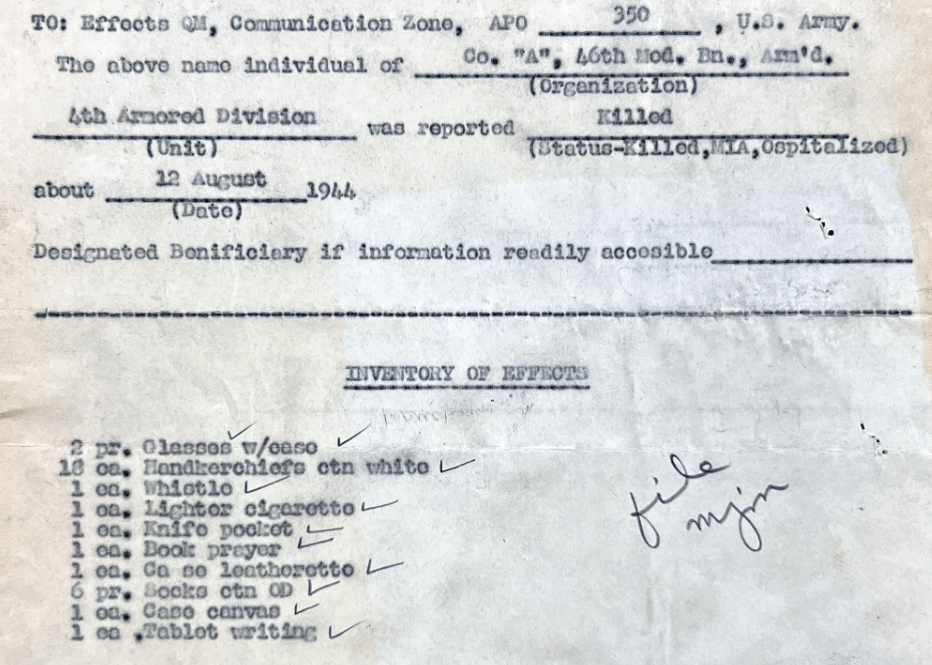

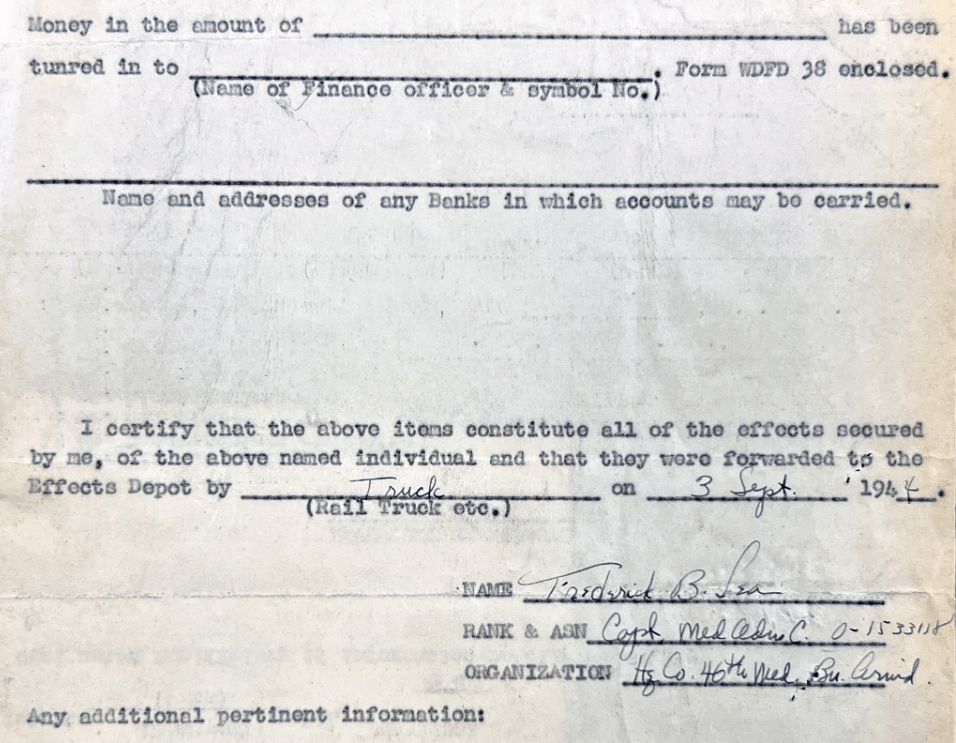

The personal effects of the deceased were collected both at the cemetery, where all the effects carried on the body were collected, and back at his unit, where all the personal items not carried on the body were collected.

Personal effects list Report of Burial

Personal effects list from 46th AMB, same casualty

All these personal effects were sent to the Army Effects Bureau of the Kansas City Quartermaster Depot, where they were inspected, sorted (and any unwanted items removed), and cleaned before they were returned to the next of kin.

Final word

With the burial of the bodies and the collection of the personal effects, the deceased personnel of the 4th Armored Division were “gone”. But it is important to understand that they were certainly not forgotten. Not then and not now!

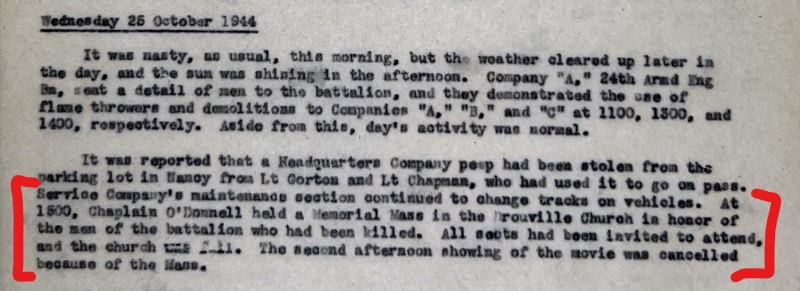

51st AIB Battalion Journal

Tec5 Jack G. Ammon, Chaplains assistent to Chaplain David W. Ray playing Taps on his bugle